In Australia, Lantana has been declared a Weed of National Significance. It’s poisonous to people and livestock. Its prickly branches form into dense thickets that overwhelm huge chunks of the Australian Bush. And it stinks, literally. So is the news about Lantana all bad?

In the 19th century, some European gardeners were experimenting with different varieties of Lantana in their hothouses. Then in the 1840s, a Lantana camara hybrid developed in those hothouses was shipped to Australia. It made its first appearance in the country at the Adelaide Botanical Gardens, and began being distributed as an ornamental shrub. Twenty years later it was starting to be noticed as a weed springing up on its own in places like Sydney and Brisbane. Around about that time, a few smart gardeners figured that the plant could turn out to be a bit of a bother. It turns out they were right: Lantana now covers approximately four million hectares of land east of the Great Dividing Range.

Lantana tends to do best where the land has been disturbed. So if you’ve been breaking up the soil by pulling out weeds then, ironically you’re helping create ideal conditions for Lantana. However, given the chance it will also take over undisturbed areas too, forming dense, impenetrable thickets 2-4 metres high. Sometimes it even climbs into trees. As it grows right over the top of other plants it blocks out the light, which inhibits their growth. And just to make things worse, it seems that the Lantana also releases chemicals that suppress the other plants.

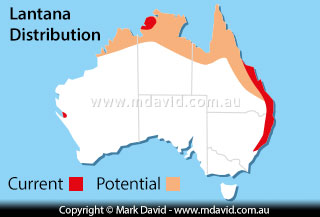

The spread of Lantana in Australia. Source: weeds.org.au

What’s it look like?

Lantana forms into dense, spreading thickets, with hairy, serrated foliage over prickly stems. Look for colourful heads of flowers. And the leaves stink when you crush them.

Where is it?

Lantana is now considered an invasive weed in more than 60 countries. In Australia, it currently grows throughout the regions shown in red on the map here. You’ll often find it along the sides of roads where the soil’s been disturbed. Left alone, it will then spread into the nearby bush.

My introduction to Lantana

1: Lantana forms into impenetrable thickets 2-4 metres high. 2: Beneath the thin layer of leaves there’s a tall, dense tangle of prickly stems.

I’ll never forget something that happened when I was young. I’ll start by saying I was one of those lucky kids who happened to live in a street that ran alongside a bush reserve. It was a fantastic place, which I especially remember for its native orchids growing all over the place. One day, a convoy of dump trucks turned up. They were trucks from the local municipal council and every one of them was piled high with Lantana cuttings. Apparently, they had been clearing the stuff out of the bush, and needed to get rid of the stuff. So they dumped it in some more bush, in the reserve alongside our street.

All that day they kept returning with their stinking loads (yep, I’ll say it again: Lantana has a strong, unpleasant smell). The Council would reverse their trucks to the edge of the cliff and in the true spirit of a vandal, dump all their Lantana over the hill. By the time they finished work that afternoon, the wild orchids were buried under tons of prickly branches.

Of course, lots of the cuttings took root and after a few years the whole area was overwhelmed by a sea of Lantana.

Even then, Council would have thrown the proverbial book at you if you were caught vandalising a bush reserve as badly as that but apparently they couldn’t manage to regulate themselves. While this story illustrates one of the fastest methods for propagating Lantana, it’s not the usual way.

How it normally spreads

I’ve already mentioned the slack-Council method, but once it’s established the plant has other ways of finding new territory.

Lewin’s Honeyeater feeding on Lantana berries

Because it grows so vigorously, its stems soon hang down to touch the ground and where they make contact with the soil they put down new roots to establish a new base. In areas with enough warmth and moisture, the plants are almost always flowering and fruiting. The berries which it produces each contain a seed. Birds eat the berries and then fly to a new area, depositing seeds enclosed in bird dropping fertiliser.

Adult (1) and nymph (2) Lantana Treehoppers on the stem of a Fiddlewood tree.

Biological control

It always seems like the obvious solution, but biological control is often easier said than done. Since 1914, a whole bunch of attempts have been made to use biological control to reduce the spread of Lantana but, whether it’s because Lantana is a hybrid or because it’s just plain resilient, it’s proving to be difficult to find critters suitable for the role. There was one little insect, called the Lantana Treehopper (Aconophora compressa), which was supposed to reduce the vigour of Lantana infestations by sucking its sap, but I guess that is not going as well as everyone hoped. What is annoying is that it’s showing a taste for a few other plants like Fiddlewood trees. For example, in the area where I live, I sometimes see Fiddlewoods absolutely covered with Lantana Treehoppers, while the Lantana growing nearby is left alone and doing very nicely, thank you.

So, is there anything good to say about Lantana?

I’m reluctant to say there is. I’ll come right out and say I hate the stuff. I would also argue that the few good things it does would arguably have been handled better by the indigenous species which Lantana has displaced. But after 800-odd words trashing its reputation I figure I might as well give credit where it’s due.

Back in the 1990s I spent a day doing some volunteer work helping a zoologist studying Little Penguins on Lion Island in Pittwater, NSW. The thickets of Lantana which had invaded and spread up the hillside turned out to be providing the penguins valuable cover each evening as they scrambled up the cliffs to their nests. Without that cover, it’s likely some of the penguins would have ended up as dinner for eagles.

1: A Variegated Fairy-wren clings to a Lantana stem. 2: Another Fairy-wren spotted in the Lantana. This one is a Red-backed Fairy-wren. 3: A Richmond Birdwing butterfly pauses for a fuel stop at a Lantana flower.

And lately, I’ve been deliberately heading for Lantana thickets, especially where it’s growing near water, to get photos of Fairy-wrens. These sweet little birds, and other small animals, love the cover it provides. The prickly tangles of branches provide the small birds with plenty of protection from predators. There are lots of butterflies that enjoy feeding from the Lantana flowers too, include the spectacular Richmond Birdwing butterfly.

Where to from here?

I sometimes think Australia is in the middle of a giant long-term experiment. This island continent had been isolated from the other land masses for so long that it developed a truly unique flora and fauna. But in the last 200 years the resulting mix has been muddled with an ever-increasing influx of new plants and animals from around the world. Placed into suburban and botanical gardens, exotic plants give the impression of being immovable things. But imagine a time-lapse recording of the spread of Lantana over 150 years. You’d realise that even something rooted into the ground can manage to spread itself far and wide, often with completely unexpected consequences.

Now I don’t want to suggest that every exotic plant species is going to run rampant through the bush. For example, the English Rose has been in Australian gardens for ages and yet I’ve never seen a hillside overtaken by wild English Roses.

I’ll end this article with a scary number. According to the Australian Government, more than 28,000 exotic plant species have been brought into the country and of those, about 2,700 have escaped to support themselves in the wild. Some of those plants are already running riot across the landscape and some of the others are what we call ‘sleeper weeds’, meaning that while they are not doing much at the moment, things could be different if something like the climate changes in their favour.

Considering that it took 150 years for most Australians to grasp the implications of releasing Lantana into the country, I can’t help wondering what we’re doing to this place, and what the Australia will look like in another 150 years with those 2,700 other species that have escaped to live in the Australian environment.