How the 3D cow illustration was made

There are lots of steps involved in using 3D software to make an illustration and

plenty of really good information about the subject already published, in books,

magazines and online. So I won’t try to explain everything here. Instead I’ll

show you the basic stages.

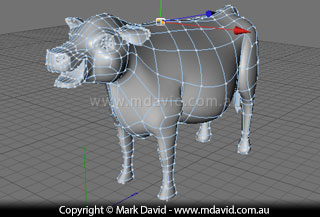

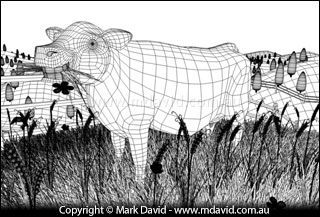

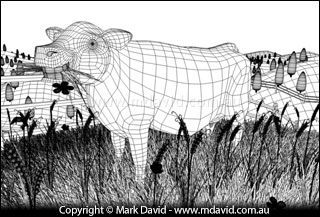

First thing is to model the cow. 3D artists talk about how easy 3D software is to use,

and once you’ve learned how to use it, it’s true that you’re able to work

quickly. But it’s not so easy to learn! I use Cinema 4D because when I bought it, it

seemed to have the easiest learning curve among the various packages, but if you want to do

this kind of stuff, expect to put in lots and lots of hours.

Whenever I model an animal I always start with the head. Here’s the first stage of

the cow model.

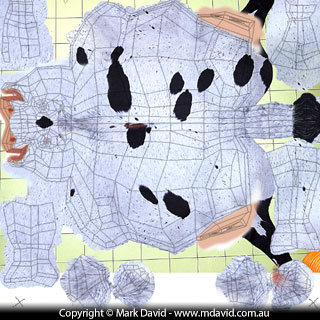

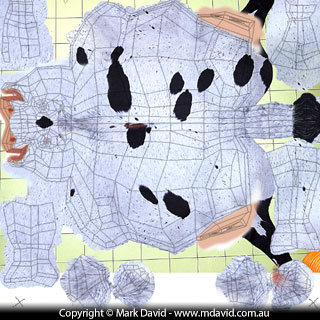

When it came time to put spots onto the cow I didn’t try to simulate a cow

texture. Instead, I took a photo of a cow skin rug. This resulted in a pattern much more

realistic than anything I could make up.

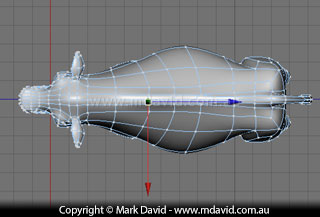

This picture shows a flattened version of my cow mesh with the cow rug spread over

it. That allowed me to line up the spots with the cow’s geometry. I used software

called BodyPaint to map the texture onto the mesh. It lets me see the

flattened surface of the cow in the same way as a map of the world lets us see a flattened

surface of the globe. That’s why 3D artists call this process ‘mapping’.

You’ll see I’ve made a few changes to the cow skin and also painted in some

of my own colours so things like the cow’s lips are the right colour.

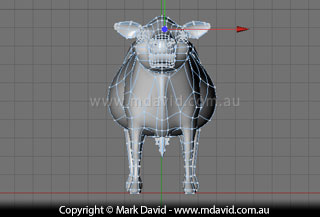

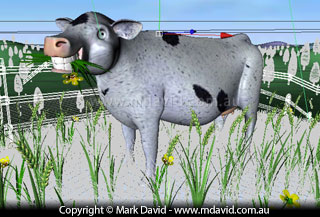

I’m satisfied with how the texture wraps around the cow now. I haven’t

bothered modelling the hooves because I planned to have them mostly hidden by some long grass.

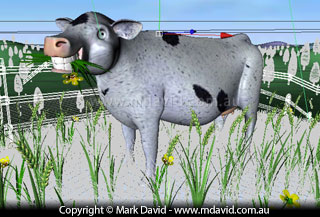

Here’s where I put the cow into a landscape. I couldn’t resist the

classic idea of rolling green hills. I used the same Cinema 4D software which I’d used

for the cow to make the hills, the fence and the foreground grass.

I modelled a wheat plant and flowers, which I duplicated lots of times around

the cow. If you rotate them a bit each time you use them, it tricks the eye into seeing

them as all being different.

I’ve finished the job of putting materials onto everything and am ready

to get the computer to ‘render’ the scene. It looks a little bit strange

because I’m only showing it the way I see it when I work on it with the computer.

But rendering will change all that.

During the rendering process the computer does all the hard work. It makes an assessment

of every part of the scene I’ve assembled and draws up the final image, pixel by pixel.

During rendering the computer makes decisions based on the modelling, texturing, lighting

and any other effects going on in the scene. It can take a long time.

How much time, depends on a whole lot of things, like for example, how fast your computer

is, how many objects are in the scene, how complex those objects are, how many lights are

used in the scene, and how big you want the final image to be. To render this image big

enough for, say, a half-page magazine illustration would take about 10 hours on an old

computer or about an hour on a new one.

Here’s a close-up view of the finished illustration after it had finished rendering.

I’ve opened the rendered file in Photoshop and painted a bit of fuzzy hair around

the top of its head and ears, but the 3D software did everything else in the scene.