As humans clear forests and replace them with farms, roads, buildings and ornamental gardens, they’re creating niches that suit some animals more than others. One bird that’s doing very nicely out of this arrangement is the Rainbow Lorikeet.

What do they look like?

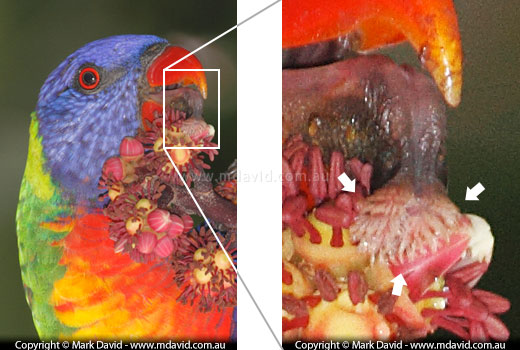

The ‘Trichoglossus’ part of their scientific name, Trichoglossus haematodus, means hairy tongue, which is a good description because lorikeets have hairs on their tongue that help soak up nectar.

But when I look into a tree full of Rainbow Lorikeets it’s not a bunch of tongues I’m seeing. These birds have a distinctive appearance with a blue head and red beak.

Surprisingly, for such a colourful bird it can sometimes be difficult to see them in a tree, and it’s their raucous screeching, squeaking and chattering rather than their plumage that lets me know they’re around.

The arrows point to the little hairs on this Rainbow Lorikeet’s tongue.

What do they do all day?

Rainbow Lorikeets spend most of their days feeding. They’ll happily go for flowers, pollen, nectar, seeds, insects and fruit. They often take over a tree in swarms, especially trees with ripening fruit. I used to live in a place with a giant fig tree outside my bedroom window. When the figs were ripening, the fruit bats would arrive to screech and fight over the fruit all night. Then at the crack of dawn the bats would leave and the Rainbow Lorikeets would sign in for the day shift. I didn’t get much sleep at those times.

This habit of taking over fruiting trees has created a problem for Northern Territory farmers, some of whom lose most of their fruit crops to these birds.

1: Rainbow Lorikeets can be easy to notice, thanks to their colourful plumage and the noise they make 2: These birds love feeding on nectar-rich flowers

Making a nuisance

During the day they tend to stay in small flocks, but close to sunset they will often assemble into giant roosting flocks of up to a thousand, taking over stands of trees and creating a deafening racket. Like the Indian Myna, these birds often prefer to form these giant roosting flocks in places with lots of human activity, like shopping centres. I’ve seen large numbers of the birds in busy areas near shops in Dee Why (NSW) and alongside the river at Noosaville (Queensland).

I remember one poor gum tree at Noosaville which the lorikeets seemed to prefer and it was almost completely stripped of leaves by the playful clipping from the birds’ sharp beaks. To walk under the tree when the birds were roosting was to walk through a light rain of shredded leaves. So I guess that wasn’t much good for the tree. The noise those birds, and the hundreds of others in nearby trees made, was outrageous. It was literally painfully loud, and they didn’t seem the least bit worried by having shops, people and cars around.

1: Rainbow Lorikeet examining a potential nesting hollow 2: Despite their vivid colours, they can be surprisingly difficult to see high up in a tree.

East vs West

A common mistake people make is to think that, because an animal or plant is Australian, then it belongs in every part of the country. But the term ‘Australian’ is a human concept that has little to do with how the ecology of the continent had become established before humans arrived. It’s a bit like trying to say that any bird indigenous to Hawaii is indigenous to all the other states in the USA. Nature doesn’t pay that kind of attention to our political boundaries.

1: Rainbow Lorikeets feeding on a fallen mango 2: Scaly-breasted Lorikeets are sometimes mistaken for Rainbow Lorikeets and will often be seen feeding alongside the Rainbows. However, the Scaly-breasted Lorikeet lacks the blue head.

Likewise, the Australian continent is a vast place with some very extensive dry regions separating the east and west coasts. The ecology of each coast had plenty of time to develop differently, and releasing an east-coast bird into the west-coast environment can upset the local balance. In his excellent book the new nature, author Tim Low describes how in South Australia, Rainbow Lorikeets are considered as big a pest as starlings because they bred up into big numbers and are eating their way through fruit crops. He also tells a story about how Rainbow Lorikeets, perhaps released or escaped from captivity, took over some of the best nesting holes in Perth, on some occasions attacking local birds that were already in the holes, and killing them.

The fact that they like to make their nests in tree hollows is significant too, because there’s already a shortage of good tree hollows around the cities. That’s because big old trees are chopped down or pruned before they drop branches, reducing the chance of a decent hollow forming. So all the birds that need hollows for their nests are already finding things tough, and now they’re getting increasing competition for nesting spots from aggressive birds like Rainbow Lorikeets and Indian Mynahs.

Fast breeders?

There’s a bit of debate going on about how fast Rainbow Lorikeets breed. Some people say they can have up to three clutches of eggs in a season, while others claim it’s more likely they have one clutch of 2 or 3 eggs in a season.

I count myself as lucky because I get to see these birds a lot. They are fantastic creatures. But as much as I enjoy seeing them, I’m convinced it’s best not to release them in places outside of their original range.

A few more things about them

- Rainbow Lorikeet mating pairs stay together for life

- They’re eaten by falcons and pythons

- They can live for about 20 years

Reference

Some of the information in this article came from:

Tim Low. 2002. the new nature. Viking (Published by the Penguin Group, Australia)