PAGE 1 | PAGE 2 | PAGE 3 | PAGE 4 | PAGE 5 | PAGE 6 | PAGE 7

October 21, 2012

This tree frog was perched in the bright pink foliage of a cordyline plant. Cute little fella eh? I’ve been getting a lot of really nice feedback about my frog photos so I thought I would do a new article explaining how I take them. You can find it here.

October 21, 2012

A lot of people don’t realise that kangaroos can swim. Here’s a very large Eastern Grey Kangaroo buck swimming in water at least 20 feet deep. He’s going pretty fast too, as you can see by the wave he’s making.

I don’t know why he decided to swim. Maybe he just wanted to cool off, similar to how many dogs enjoy a plunge in some water on a hot day. But seriously, your guess is a good as mine.

October 9, 2012

It can be disappointing to take a bunch of photos and see them coming out with way too much contrast. This is especially common with photos of black and white animals. Of course what I’m leading to here, is an understanding of dynamic range. Yep, dynamic range is how much of a difference there is between the light and dark in your scene. If the difference is too great your camera’s going to struggle getting detail in all the bits you might want it. So I’ve written a new article to explain how to deal with it.

October 8, 2012

I got a really nice email from a fellow who’s been feeding wild birds. This guy sounded like someone who has put a lot of thought into what he gives to the birds, how often he feeds them, and so on. And it got me thinking about my own article on feeding wild animals.

In general, I’m not a big fan of the practice of feeding wildlife. But that doesn’t mean it can’t be done in a good way. I figured my article in its existing form only concentrated on the negative, so I’ve updated it to give what I hope is a more balanced view.

September 30, 2012

I’ve just done another article. This time it’s about ‘resolution’. In digital photography, resolution can refer to what’s happening in your image, your screen or your printer. And the word adopts a different shade of meaning each time. If you take photos, it’s just assumed you know all this stuff, but some people don’t. Especially those who are unfamiliar with software like Photoshop. I’ve spent the last 20 years immersed in this subject as my ‘bread and butter’ business. Here I explain the most important parts of the subject in the simplest way I can.

You can find the article in my photography section here.

September 17, 2012

With the warmer weather lately, the place around here is filling up very nicely with tree frogs. So I’ve been back out there with the camera this morning taking more pics of the little guys. Each of these shots was taken with a Canon 7D, 100mm macro lens and a tripod.

September 16, 2012

I’ve just put a new article online. It’s a guide to wildlife photography, summing up a bunch of things I talk about in other articles, plus some new stuff. If you want to get better shots of critters then here’s where to find it.

September 8, 2012

It’s distressing to see so many beautiful sea birds caught up in fish hooks and fishing line. In two consecutive trips to a popular river picnic area I noticed a pelican and a seagull unable to free themselves from some fishing line. In the case of the pelican, the line was attached to a big, rusty hook in its neck (see small image at left).

The seagull (above) had its feet tangled up in line.

If it’s frustrating from my perspective as a photographer, I can barely imagine what it’s like for the birds.

August 28, 2012

Photographing one critter can be great, but things can get heaps more interesting when animals interact with each other. Animals do a lot of their communication via body language, and catching that body language can introduce a lot of ‘story’ into your shots.

Sometimes the action breaks out into a fight, in which case the conflict will usually be all over in a few seconds. If the conflict lasts longer then the animals might be oblivious to everything else around them and so that can offer a rare chance to move in closer with your camera. (Of course, I’m only talking about the kind of wildlife that is safe to approach!)

During those sparring matches, you need to be able to freeze the action. 1,000th second exposures will the slowest you can go unless you want a lot of motion blur. Taking shots in a fast burst (rather than trying to time individual exposures) will increase your chances of getting a keeper.

The alternative is the use of flash to freeze the action in dimly-lit scenes. That can work well, but you might see a little bit of motion blur from the slower shutter speed. You see, cameras need to slow down their shutter speed in flash photography because otherwise it’s too difficult for them to time the flash to go off when the shutter is fully open. If you want to find out more about this, the thing to look up is called the ‘flash sync speed’.

So next time you’re out photographing wildlife, keep an eye out for the things that happen when animals encounter each other.

August 22, 2012

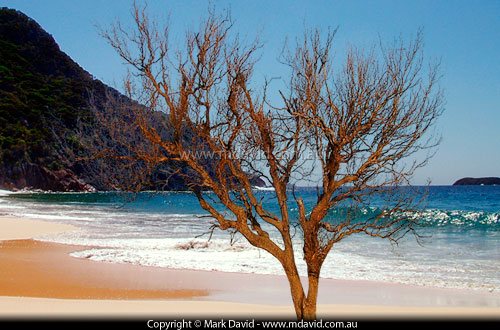

Imagine you had to cut the tree out of the photograph above and stick it into a new background, and imagine you have less than two minutes to do it.

This is a trick I often used in my job as a production artist at a newspaper. I’m talking about super-fast deep etches of crazy-complicated objects.

Lots of people have asked me how I do it so I explain how — a sneaky way of using Adobe Photoshop’s channels to deep etch (mask) an image — in a new article I put online today.

August 21, 2012

I’ve just put a new article online about the experience I had getting rid of Cane Toads from our block of land. Dealing with the toads (humanely) was a lot easier than I thought it would be. And we got benefits that we never expected.

August 17, 2012

Can light ever be too good?

There’s been some hazard-reduction burning going on around here lately. That puts a bit of smoky haze on the horizon. Providing the smoke is not too heavy then I don’t mind it all — it provides a great golden light just before sunset, and that light pumps the most fantastic rich colours into your shots.

And I’m a real sucker for bright colours in my photos.

So I’m out walking with my camera and the landscape is flooded with colour and then I see hear some Rainbow Lorikeets nearby, which just happen to be insanely colourful birds.

You know where this is leading don’t you. What happens if when you try to use the insane colour-intense light on an insanely colourful bird?

The result is interesting, but also quite predictable. Rainbow Lorikeets have bright blue heads. And if you put a blue thing into orange light it looks sort of black.

The pictures above give you an example. You can see the golden tinge in the branch and of course the reds and yellows glow so brightly that it almost felt like it was burning my eyes just to look at them. But look at that blue head. There is no post-production trickery going on here. Thanks to the laws of physics we have a black-faced Rainbow Lorikeet.

To prove the point, I’ll show how one of these birds looks like when photographed with Flash (above). You’ll see that we’re not even talking about dark blue.

July 30, 2012

Here are some pics of the Cattle Egrets roosting. They usually pick just one tree and then the whole lot of them roost at the very top of it, giving the birds a clear view of the surrounding landscape (which makes it suprisingly difficult to approach the tree on foot without alarming them). Sometimes the weight of so many birds will snap the growing tips off the tree, which causes the tree trunk to branch and start growing crooked.

July 29, 2012

I’m a big fan of the light you get just before sunset. I’m a bit of a fan of Cattle Egrets too. So lately I’ve been trying to combine the two.

Cattle Egrets are pristine white birds, but the late afternoon light makes them glow orange. When you photograph them with the sun behind you, they light up like a neon sign. When you photograph them with the sun behind the birds, the orange shines through their wings, showing off the overlapping feathers.

After a day spent hanging around with cows, these birds fly in from all directions to settle in large numbers at the top of their roosting tree. Which is great, except they don’t use the same tree each night. That means it’s tricky to decide where to wait for them. So I usually follow a few of the early birds and then take my shots as more groups approach.

Although it’s not always small groups. Sometimes a hundred or more will fly low overhead at once. The sound that many birds makes is very beautiful. There’s no squawking, or hooting like when Magpie Geese fly overhead. No, it’s almost completely quiet other than the slightly eerie sound made by a couple of hundred wings flapping at once. And while all that’s going on, the late afternoon sun makes them glow like they’re on fire. At times like that, it’s easy to forget to take photos.

You’ve got to approach their roosting tree carefully too. Because these birds are very easily spooked. An abrupt movement from even a hundred metres away can cause the whole flock to take off from the tree top in an explosion of flapping wings and wrecked photo opportunity.